Back in the early '70s, when I first became aware of Clint Eastwood the cop, the cowboy, the action figure, there was talk about the dangerous examples set by his characters' violence and impatience with the judicial process. Was our culture as vulnerable then as it is today? Was it as liable to imitate its entertainment? Who was Dirty Harry? Was he a right-wing avenger or a soldier of common sense?

Artists have responsibility for the images they paint of the culture and for understanding what their intent may stimulate in interpretation and imitation. However, art is always subject to imitation by misinterpreters of its intent, and it is then that the artist's prior sense of responsibility is a somewhat forlorn and ineffectual thing, for which the artist is no longer accountable. Poisonous art is not so much a function of counterproductive messages as it is a creation of the inauthentic messenger. When Eastwood brought down the Bad Man with his Big Bad Gun, his own authenticity, humor and sense of cinematic vitality guided the impact of his bullet. Eastwood is an authentic messenger, a jazzman and a gentleman. And because he is so genuine, his audience is safe in his hands.

It seems ironic that Million Dollar Baby should have put Eastwood in conflict with the hordes on the political and religious right. Those very factions have for decades hijacked his persona of heroic, moral stoicism and virtuous strength. But he has never been at the service of any political or moral extreme. He is, indeed, the best of our center — where its core is one of gravity and heart.

The gun-toting, square-jawed Eastwood made a love story last year. And perhaps only such a mature and courageous filmmaker could have seen that love story through the haze of political incorrectness, euthanasia and the brutality of pugilism. It is his uniquely strong center, yet he shares it with his audience. They are touched, inspired, even angered.

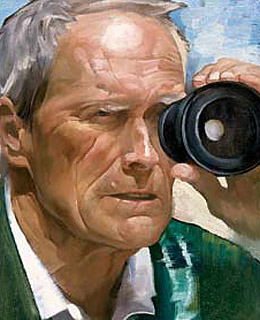

As actor and director, Eastwood delivers American haiku in cowboy boots. His approach and eye, of such seemingly simple humility, are both indelible and profound. At 74, he has become cinema's Mount Rushmore. The handsome lined face, the quiet gravelly voice and the alternately smiling and somber eyes are the embodiment of American film. Past, present and, most of all, center. Yes, Clint. Punk feels lucky.

Penn won an Oscar for his role in the Eastwood-directed Mystic River